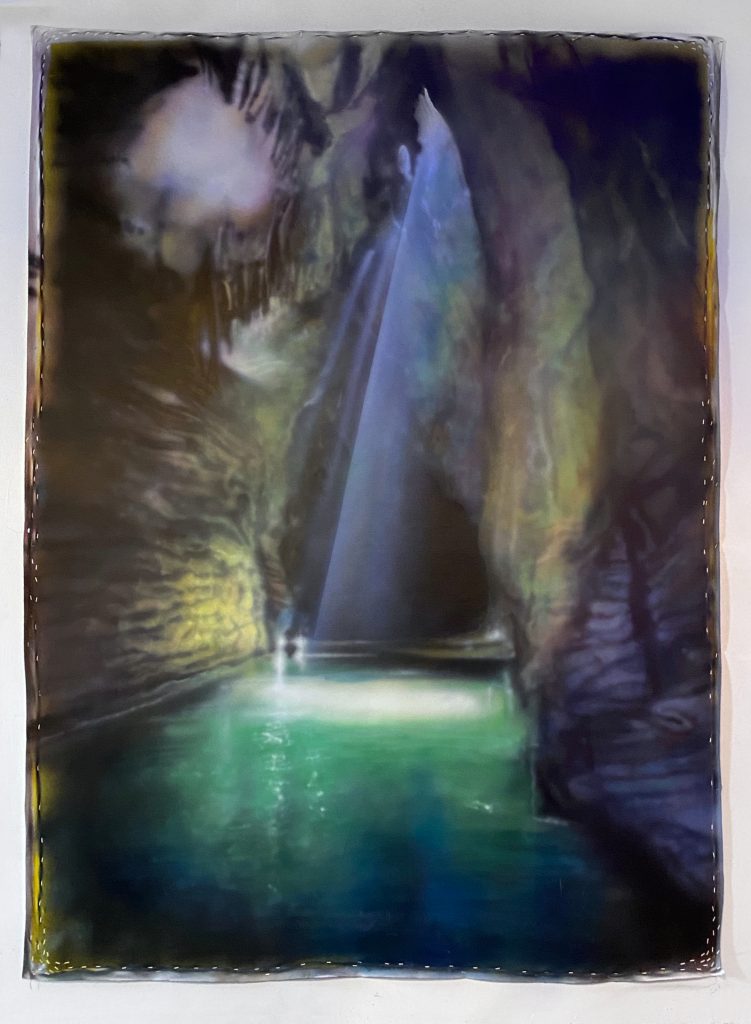

INTERNATIONAL WATERS: CONTAINER GARDEN

Opening: Friday February 7, 2020

9pm – Midnight

Music by @princesssombra

For the inaugural exhibition of International Waters , Container Garden brings together the works of Emily Janowick and Sam Cockrell. Janowick and Cockrell’s work uses the container as a metaphor to describe the structure of our constructed natural landscape. The container is defined by its border. For Janowick and Cockrell, the container refers to the womb, the body, the monument, the city… “the tool that brings energy home.”

Janowick has produced a 24 foot model of the Washington Monument that lies on its side. Taken from the Egyptian obelisk, the Washington Monument was made to commemorate George Washington and does little to recall the sun god Ra who’s physical form is symbolized by the structure. Falling down the sloping floor of the gallery, Janowick’s obelisk is hollow. Inside the monument, a two-channel video of the artist’s father and daughter plays.

The videos show both of them having a conversation about beginnings, middles, and endings. Her father is sitting in a plastic box while her daughter is sitting in a bathtub. The dialogue is taken from the last scene of the 1998 film Hope Floats. “We don’t just gather the physical, we narrate our world through the stories we carry. It’s how we build history. How we tell our stories fundamentally changes who we are and how we think of ourselves. We are like Matryoshka, vessels within vessels, carrying stories, culture, genetic material and cellulite.”

Solid State from Emily Janowick on Vimeo.

The monument for Janowick is always changing. Its meaning is tied to the ruling class and therefore can change with history. As a container, the architecture of the monument is a vessel for content — but a poor one. “Containers can serve their function only if they change more slowly than their contents.” The combination of Janowick’s intrapersonal narrative with a nationalistic mythology suggests that monuments are forever in flux; they are objects determined by form moreso than content.

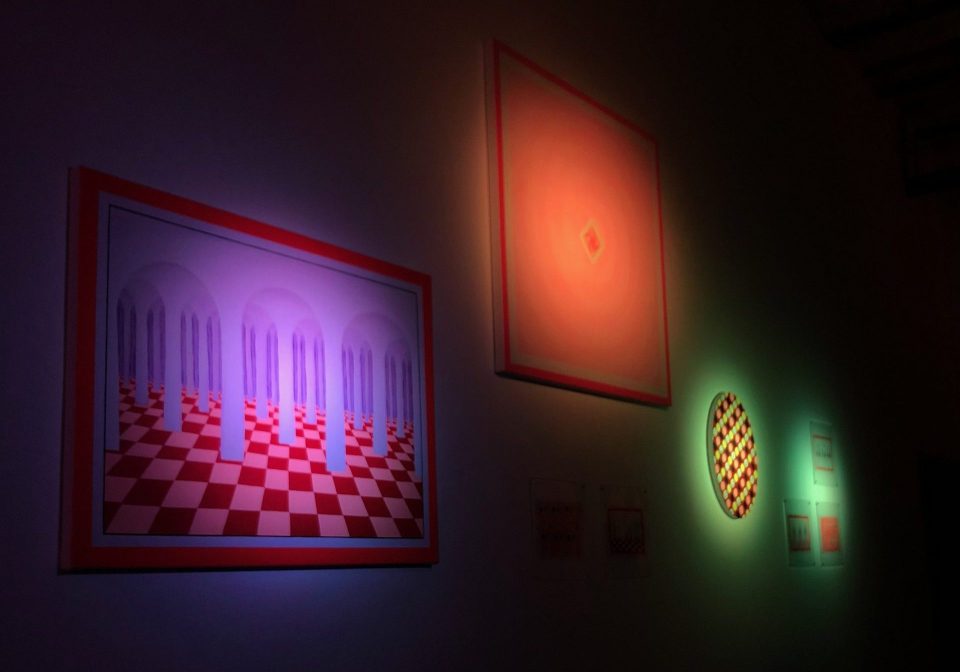

Taking inspiration from “that bullshit minimalist [Josef Albers]”, Sam Cockrell calls attention to Uhaul Trucking Venture Across America and Canada SuperGraphics ad campaign. SuperGraphics, seen on the side of Uhaul trucks, each describe a different anecdote for all of the states and provinces of North America.

For Cockrell, the Uhaul truck is an icon for art handling and the standardization of mobility. The SuperGraphics provide an iconoclastic narration of the physical landscape that they allow anyone to conquer with possessions in tow. As an object, the Uhaul is inscribed with the aesthetics of the natural world while its contents are hidden under layers of SuperGraphics. A vast network has been stretched across the natural landscape to allow for an unencumbered free-flow of commodities across land and sea. The Uhaul allows anyone to access the vast network with the same aesthetic principles of a human-user-interface.

Containers contain containers. Although the container outwardly is the holder of content, perhaps the greater dissemination of content comes from the container itself.

“The hero as bottle, a stringent reevaluation. I now propose the bottle as hero. Not just the bottle of gin or wine, but bottle in its older sense of container in general, a thing that holds something else.”